This story is part of a series produced by En El Camino by Periodistas de a Pie, and funded by the Open Society Foundations. It has been translated pro bono, and without permission, by the Mexican Journalism Translation Project.

My Country, You Are Watching Me Leave

By Rodrigo Soberanes Santín (En El Camino, Periodistas de a Pie)

What lies behind the numbers of tens of thousands of migrants who cross the border each year? Statistics suggest that people in their tens of thousands cross into Mexico without migratory documents – mostly from Honduras. But these figures don’t explain the reasons behind the exodus, for the misery and violence that permeate their countries of origin. For those who have left, and for those about to leave, the absence of the future leaves them with few options: stay to die a slow death, or risk their lives in a hellish journey.

Progreso, Honduras.- José Luis places his artificial limb on his leg, puts on his shirt with only one sleeve, and places a bandana around the only finger on the only hand he still has from that day in the Mexican desert.

He opens the door, passes the ongoing construction site that one day, he says, will house his family when he is married, and goes out into the street in search of a family that has a story of migration to tell him. He is president of the Association of Migrant Returnees with a Disability (Asociación de Migrantes Retornados con Discapacidad), and he has a remarkable interest in familiarizing himself with all the cases of forced migration from his country; he offers himself as a guide to know their stories.

For many years, José Luis has been well known in this city. Famous at one time for his talent singing rancheros and religious songs, eight years ago he lost his arm, a leg, and four fingers when he fell from a cargo train. It was his second attempt to reach the United States as an undocumented migrant. That’s who he was when he came back to Progreso and so he became involved in accompanying those who experienced the same thing he had lived through.

Honduras, his country, is the place most Central American migrants leave to go north. The flow of migration from Honduras has the greatest human cost in the world. Progreso, his city, is one of Honduras’s principal manufacturers of manpower ready to undertake the journey.

The journey north seems to be everywhere but above all else in those places where the exodus begins. When the drivers and their helpers have enough passengers, the buses parked in the city’s dilapidated central bus station can leave. The first buses to go are those for San Pedro Sula, a good place to leave the country. Then, when they enter Mexico, they are in the land of murders, fatal accidents, kidnappings and disappearances.

The Mesoamerican Migrant Movement labels the region the place of “migrant genocide.”

Before 1998, when Hurricane Mitch destroyed Honduras, Progreso was a place that attracted workers from the country’s south because of its banana industry and its factories. Today, its streets bear the marks of what forced migration gives and takes: houses constructed from material but with fractured families; small businesses and fast food restaurants that mingle with this place’s customs; places to receive Western Union remittances that spring up like businesses mining migrants’ savings.

A walk around Progreso’s streets and one finds Claro telephone stalls belonging to Mexican business magnate, Carlos Slim, and brimming with clients complaining about the poor service. Further on, in the dusty peripheral neighborhoods, residents leaving work avoid the darkness so they won’t be assaulted. Day laborers from the last of the banana plantations, industrial workers, taxis, office workers, and the unemployed – all of them are somehow linked to migration.

“Most of them were, or will be, migrants,” says Javier, a factory worker.

His eleven year-old grandson Anthony is with him and asks, “Is Honduras beautiful?” He replies that it’s not because “anybody can pull a pistol on you.”

It won’t do anything for Anthony to remember all the beautiful things about his country. Neither the Copán ruins, nor the Caribbean port of Puerto Cortés, nor the marvels of the sea around Atlántido, and not even the impressive mountain ranges of Santa Bárbara. He is growing up in a crumbling country.

Meanwhile, surefooted, and dextrously dominating his prosthetic leg that hangs halfway down his right thigh, José Luis walks under the intense Honduran sun, pointing at the houses built with dollars from migrants’ remittances, the country’s principle source of income.

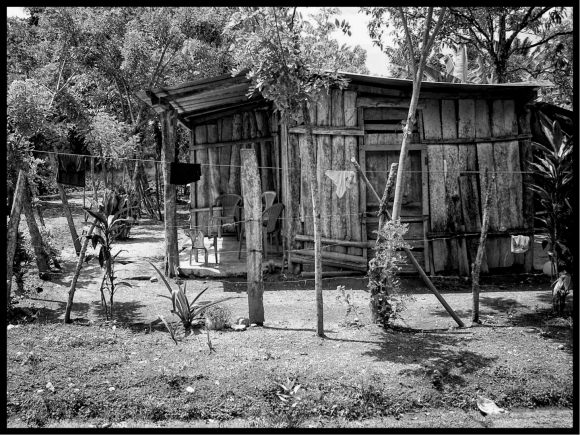

They are houses that break the mold, built according to their owner’s criteria. They have painted walls, space for a car, for several rooms and they are covered with anti-theft devices. Each house represents a survival story. More light enters their windows.

“There are a ton of houses built thanks to migrants’ remittances, those who risk their lives on the journey. Here in Progreso, and especially in this neighborhood are the roots of migration, where there are orphans because parents left and there’s significant family disintegration because of migration,” says José Luis.

In the same block there are other houses that are concrete blocks with plastic roofs, built by Honduras’s government through its social housing program. These are the homes where nobody sends back remittances.

Karla lives in one of these houses. She’s seventeen years old. She still hasn’t left.

Yet.

THE COUNTRY THAT WAS

Guido Eguiguren, a sociologist from the Association of Judges for Democracy (Asociación de Jueces por la Democracia), a Honduran human rights defender, explains forced migration in his country taking place after Hurricane Mitch, in October 1998.

“The hurricane didn’t just physically destroy the country, its infrastructure, and thousands of lives. It also showed the world a country it barely knew, with a staggering level of inequality, a country forgotten by the world of development and cooperation. A country known for the nasty role it played in the 1980s acting as the United States’ aircraft carrier.”

While El Salvador and Nicaragua were battered by civil war, Honduras lent its territory to train the armed forces of the governments of those countries.

Honduras is a country of poor people where 66.5 percent of its residents do not have sufficient income to feed themselves. It’s also an unequal country that spits on people like José Luis or Karla as they look for ways to survive: 10 percent of the richest people in the country have an income equal to that of 80 percent of its low-income population.

Honduras shares first place with Guatemala and El Salvador for pushing out migrants to Mexico, and it takes first place in the divide between rich and poor. In terms of inequality in the Latin American region, Honduras take third place, Guatemala is in fourth, and El Salvador comes in at number seven.

Nobody knows for certain how many Hondurans leave their country each year, and it’s a figure that the government does not want to give out. The rough estimate by the Catholic Church’s Pastoral for Human Movement comes from counting the numbers of people deported from Mexico and the United States: in 2013 it was 72,000 Hondurans, including children and babies.

From Monday to Friday, deportees arrive in two airplanes every day at the Center for Returnee Migrants (Centro de Atención al Migrante Retornado, CMAR) at the San Pedro Sula airport, 30 kilometers from Progreso. Men and women get off the planes who left the country free and who come back with their feet bound in tape, their wrists in chains, and with a half-empty sack as their only baggage.

They walk a few steps on leaving the plane, look around from side to side and leave the airport terminal. In a few days, maybe at that very moment, they will undertake the journey back, starting from scratch.

José Luis, who is normally a chatterbox, keeps silent when he sees them arrive, recently unbound and thankful that their country greets them with a “baleada,” a meager flour tortilla covered in beans.

It’s a brutal brush with reality. When they return they are even poorer, more vulnerable, and more exposed to the violence that forced them to flee in the first place.

THE COUNTRY THAT IS

José Luis lives in a street in the San Jorge neighborhood, a barrio established by Jesuit missionaries at the beginning of the last decade after Hurricane Mitch “positioned” itself for a day and a half over Honduras, inundating the country with the water and wind of a category five hurricane, the most furious of them all.

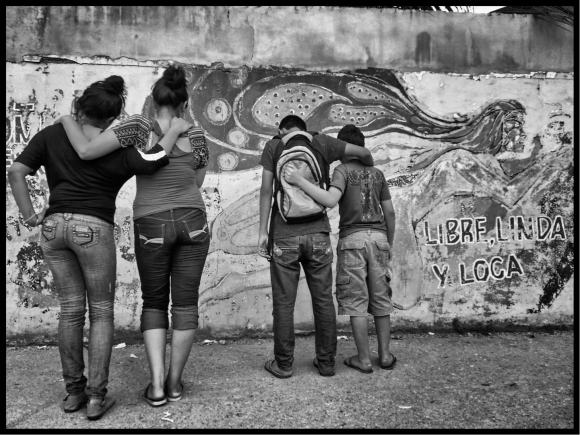

Today San Jorge is controlled by two spies (“banderistas”) of the Mara Salvatrucha who report to their bosses who comes and goes. Its four entrances are guarded by the “güirros”, some young men recruited by the Maras and armed with pistols that scare everybody. Instructions from the underworld that extend throughout Progreso come from the hill above, behind an imaginary curtain that marks the barrios’ borders.

Manuel de Jesús Suárez, communications officer of the team of Reflection, Investigation and Communication, an organization that tries to understand the causes of migration from Honduras speaks about the country it is now.

Previously, migration used to occur as an escape from poverty. Today it is a way of saving one’s life, escaping from the daily violence that is permanently in the street, house, and in the Honduran government.

“The causes of migration are not conjunctural but structural, meaning the lack of work and decent salaries, access to health, to education, to housing. Now the other phenomenon is violence, organized crime, and the drug business shaping the country’s structure. The causes are a cyst in the system. They are there. The system makes it so that the majority of the poorest men and women remain excluded and so they leave,” he explains.

Manuel de Jesús, a man of more than 50 years old, knows this history well. He was born in Progreso and he has seen the collapse of the factories and the banana plantations, along with the arrival of the U.S. fast food outlets that spew out their greasy odor in the chaotic streets at the heart of the city. Wendy’s outlets, Burger Kings and Pizza Huts – all have armed guards with shotguns stationed inside their branches.

In 2013, 9,453 people died in Honduras for “external reasons”, meaning they were victims of violence. Of these 71.5 percent were murdered. In this country where an undeclared war rages, 563 people die each month. That’s nineteen deaths every day.

These numbers mark Honduras with the highest homicide rate in the world.

DISPOSSESSION AND DERELICTION

José Luis walks Progreso’s streets with mastery on his only leg. The sounds of radios drift from the windows of houses. Radio Progreso was established by Jesuits. On a Sunday program serving as catharsis to confront the abandonment, the station covers work problems, neighborhood violence, the educational system, human rights and migration.

The signal that can be heard from these windows accompanies people whose families have been broken. A migrant comes on the air to tell how, when he left Honduras, “another cock feathered his wife” and his wife left him. The calls keep on coming. Mostly on the radio one hears about those who live or lived with some consequence of forced migration.

The presenters on the Sunday program are Rosa Nelly Santos and Marcia Martínez, members of the Committee of Relatives of Disappeared Migrants (Cofamipro), and on this occasion they are talking about family disintegration. Before moving to a break in the program, Rosa Nelly announced the tune Hermano Migrante (Fellow Migrant) by Natividad Herrera who sings, “Return soon and enjoy what’s yours / forget the crying and all that pain.”

Return home; fill the towns with people that migration took north. Progreso, like many communities and barrios in Central America has been slowly emptied in the past year. Houses remain behind, sometimes empty, but most half inhabited.

Behind every door and window lie fractured stories.

LIFE, MUTILATED

The year was 2005, and it was José Luis’s second attempt at going to the United States. He and his friend Selvi took nineteen days to reach northern Mexico; those days were uneventful. They traveled from Progreso without stopping. They took the train in Tapachula, Mexico. They arrived in Chihuahua. They were going to cross the border at Ciudad Juárez-El Paso.

For José Luis, the success of the journey consisted in not leaving his friend while he slept on the train. He annoyed him. He spoke to him. He made him angry and he kicked him. He didn’t want him to fall asleep.

José Luis – a good footballer, guitar player, and fan of fishing in the Ulúa River bordering Progreso – sat beside the train wagon’s gears and stretched forward to tie a shoe. Strange thing: sweat covered the whole of his neck to the top of his head. He had never been in the desert. The train entered the city of Delicias and José Luis blinked.

“Suddenly things went dark and I fell. I fainted from the dry, June heat. The train severed my leg. Then I put out my arm because I couldn’t free my leg and it cut that off, too. I put out my other arm and the train wheel squashed it.

Silvi, his friend, did not realize what had happened until kilometers further on when he noticed blood covering the train wheels. He thought he was dead. He now lives in the United States where he has started a family. In the south, his friend remained behind: the man who took care of him on the train and who now moves around the streets on one leg, balancing on the arm left him by La Bestia.

Texts in Spanish: Rodrigo Soberanes Santín, for Periodistas de a Píe

I am a reporter who travels all around, mostly in Veracruz, Mexico, a good place for my job. Stories have to be brought out from nooks and crannies, and brought to the surface, like kites. Currently I work with Noticias MVS, Associated Press, Diario 19, and Jornada Veracruz.

Images: Moysés Zuñiga Santiago, for Periodistas de a Píe

A photojournalist from Chiapas interested in the struggle of indigenous communities and migration across Mexico’s southern border. I work with La Jornada, AP, Reuters and AFP. My work has been shown in New York University in 2010 and 2013. I traveled with young people like myself crossing the border in search of opportunity, taking personal stories with me that let me journey beside them. I do this work because of that; I want to make extreme situations of violence visible so that these situations don’t occur and people don’t die.

Images: Prometeo Lucero, for Periodistas de a Píe

Freelance journalist focused on human rights issues, migration, and the environment. I have collaborated with La Jornada, the Expansion group, Proceso, Desacatos, Biodiversidad Sustento y Culturas, Letras Libres, Variopinto, and among other agencies, Latitudes Press, Zuma Press, AP, and Reuters. My photojournalism appears in books such as 72migrantes (Almadía, 2011), Secretaría de Educación Pública (2010); Altares y Ofrendas en México (2010); Cartografías Disidentes (Aecid, 2008) and I have been published in other books: “Dignas: Voces de defensoras de derechos humanos” (2012) and “Acompañando la Esperanza” (2013). I was a finalist in the competition, “Rostros de la Discriminación” (México, 2012), “Los Trabajos y los Días” (Colombia, 2013) and “Hasselblad Masters” (2014).

Translation into English: Patrick Timmons, for the MxJTP

Is a human rights investigator, historian, and journalist. Follow his activities on Twitter @patricktimmons. Timmons has publications — translations, articles, or reviews — in the Tico Times (Costa Rica), El País in English (Spain), CounterPunch (USA), The Texas Observer (USA), The Latin American Research Review (USA & Canada), and the Radical History Review (USA). A graduate of the London School of Economics and Political Science (1996), Timmons holds three advanced university degrees: a Master’s in Latin American Studies from the University of Cambridge, UK (1998); a Ph.D. in Latin American History from the University of Texas at Austin, USA (2004); and, a Master’s in International Human Rights Law from the University of Essex, UK (2013).

Reblogged this on bayareaintifada.

Reblogged this on onchickenbuses.

[…] Fuente: https://mexicanjournalismtranslationproject.wordpress.com/2014/06/09/my-country-you-are-watching-me-l… […]

[…] June 9, 2014 — What lies behind the numbers of tens of thousands of migrants who cross the border each year? Statistics suggest that people in their tens of thousands cross into Mexico without migratory documents — mostly from Honduras. But these figures don’t explain the reasons behind the exodus, for the misery and violence that permeate their countries of origin. For those who have left, and for those about to leave, the absence of the future leaves them with few options: stay to die a slow death, or risk their lives in a hellish journey. […]

[…] Soberanes is based in the Americas. Follow him on Twitter @rodsantin. He is the author of “My Country, You are Watching Me Leave” for En El Camino of Periodistas de a Pie, an Open Society supported reporting project about […]

[…] Soberanes is based in Mexico. Follow him on Twitter @rodsantin. He is the author of “My Country, You are Watching Me Leave” for En El Camino of Periodistas de a Pie, an Open Society supported reporting project about […]