This article and its accompanying photos were published in Spanish under a Creative Commons License by En El Camino of Periodistas de a Pie on 3 June 2014 with support from the Open Society Foundations.

The English translation of this article has been made possible by an anonymous donation, gratefully received.

The translation of this article is dedicated to Patty Kelly, author of Lydia’s Open Door: Inside Mexico’s Most Modern Brothel. PT

Mexico’s Migrant Women, Trapped between Real and Imaginary Frontiers

By Ángeles Mariscal (EN EL CAMINO, PERIODISTAS DE A PIE)

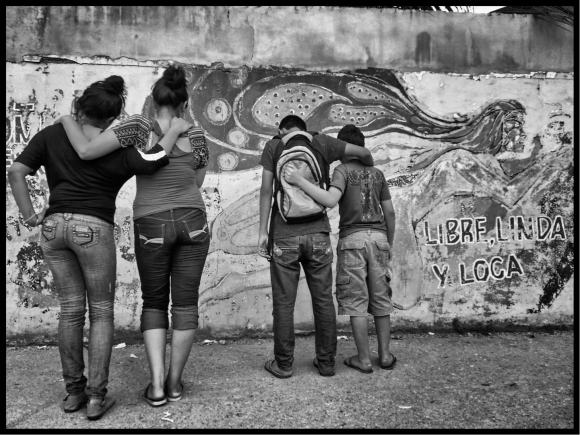

There’s a saying in southerm Mexico: Guatemalan women will do housework, Honduran women will be slaves in the bars or cantinas and the Salvadoran women are invisible. Migrant women are trapped between the physical frontier in Soconusco, Chiapas and the all-too-real yet blurry frontier where abuse, discrimination and stigmatization exist. In southern Mexico, these women aren’t anything other than what their origins – and society – has condemned them to be.

First Stigma: The “Servant” Women

It is Sunday. Miguel Hidalgo Park in the center of Tapachula – about 275 kilometers from the border with Guatemala – is packed. Dozens of women, most of them young, almost all adolescents, show off embroidered, multi-colored garments with designs and fabrics typical of the neighboring country’s indigenous people. Taking each other by the hand, the Central American women walk round and around the central kiosk.

Some arrive early, their belongings in a suitcase or plastic bag. They sit on the flower boxes and there they wait. Rosa together with two other young women just this morning crossed the border between Mexico and Guatemala, using the bridge at the Tecún Uman border crossing. They paid Mexico’s National Migration Institute for the local visitor’s visa, permitted those who live along Guatemala’s border with Mexico.

This visa allows them to cross with some freedom in the border townships. But it doesn’t let them work in Mexico. It doesn’t escape their notice that business and work tie the residents to both countries and these links go back generations and filter across the frontier.

Rosa is sweating and tired. She has just sat down on a bench when an older woman who got out of a car approaches her. Talking together, they make a deal: 1,200 pesos per month (US$92) plus food. Sundays are days off, after she prepares breakfast for the family.

The woman begins to cross the park. Rosa says a quick goodbye to her friends and falls in behind the woman. Both get into the car. Rosa gets in the back, shy. She does not look up, she avoids eye contact. Long workdays await her as a quasi-slave where she has to sweep, clean, take care of somebody else’s children and make as if she were transparent.

The scene repeats itself in the morning, here and there in the park. In the afternoon, only the domestic workers who already have a job remain, enjoying their only day off.

Girls work here as well as young women. The Fray Matías de Córdova Human Rights Center carried out a survey of domestic workers from Guatemala and found that almost half of those interviewed were 22 years old (49 percent). The other half were between 13 and 17 years old.

The Fray Matías Human Rights Center documented that the for many of the young domestic workers their expectation is to obtain funds that will let them return to their countries to continue their studies. Most only come for brief spells, but many remain trapped and return only occasionally to their native country.

There is no census or estimate about how many they are. They are a floating population and their work happens mostly out of sight, without a formal contract. Since colonial times, whether on haciendas or in homes, most of these women have naturalized the role of working as servants in the Soconusco of Chiapas

Alba has been in the Miguel Hidalgo Park since morning. She and her friends haven’t moved even though it’s been raining. Alba stands out a little more than the others. She says that she is 30 years old and that at the age of 8 she came to work in Tapachula. She is happy because they pay her 2,000 pesos per month (US$147). It’s hardly minimum wage even though her workday is twice as long as the 40 hours per week established under Mexican law.

On a regular day she wakes at 6:00, prepares breakfast, cleans, makes lunch, washes clothes, does the shopping, picks up the kitchen and irons. She has worked cleaning shops or restaurants. The pay is good, but they don’t give her a place to sleep.

“I like working in homes more,” she says, although she recognizes that she doesn’t always have her own place to sleep, like now, since she is working in a house in Colonia Solidaridad (a neighborhood inhabited by lower middle class people from Tapachula). Every night she sleeps on a mattress in the space between the kitchen and the dining room.

- What do you do on your day off?

- I help with breakfast and then I come to the park.

- Do you go out to the cinema or a nearby beach?

- No.

- Why?

- It pains me to say… the people look at us and they don’t like us being there, probably because of how we dress.

Alba says that in her country she could earn a little more money doing the same work. She prefers to stay in Tapachula because, she says, “in Guatemala there is a lot of violence.”

Santiago Martínez Junco, training coordinator for the Fray Matías de Córdova Human Rights Center explains that under Mexican law the Guatemalan domestic workers are in a system of quasi-slavery.

“The worldview of society in the region – which stigmatizes how people look – puts a mark on migrant women. If you are Guatemalan your niche is domestic work, cleaning, or agriculture. Honduran, Salvadoran and Nicaraguan women are preferred in sex work, or to attract customers in snack joints and restaurants,” he says.

The work of the Guatemalan women has been made invisible because it happens in the private sphere. This situation makes them highly vulnerable.

There are no contracts. There’s no justification when somebody is fired, a strategy often used so as to not pay wages. Sometimes they are charged for food and the average salary is between 1,200 to 1,500 pesos per month (on average, around US$100), and for about 72 hours per week.

Coupled to that, he says that society encloses them or excludes them from everyday life and places where they can meet.

“Most domestic workers don’t know anywhere but Miguel Hidalgo Park and the streets that they take to get to work. For example, people from Tapachula asked the authorities to build the Bicentennial Park because the place was “filled with chapines” (a name given to people from Guatemala). And it’s not like they can go to other places, but society pushes them out, excludes them and they feel social pressure.”

At the end of the day – confirms Santiago Martínez – they have to live in the same feudal situation that’s existed and continues to exist in this region, used exclusively as servants, not allowed to develop in other areas of work.

On Sundays, when they go for a rest in the Miguel Hidalgo Park, the Fray Matías Human Rights Center tries to make them aware of, and train them in, their rights, Martínez says.

“We tell them about their labor rights. We give them workshops in some techniques that they choose. We work dynamically so as to strengthen their self-esteem, so that they can take on their rights… sometimes we go out together in the city, go for walks to nearby places so that they begin to shed their fear and so they feel safer.”

Stigma Number Two: The Fantasy Sellers

Her body gyrates on the stage against the sonic backdrop of an accordion, trumpets and drums. Rhythmic and sensual – can a sound by itself be sensual? – the sound of cumbia accompanying the dancer while she takes off her clothes.

Under the stage at low tables, other women press their bodies to the punters, drink with them, some dance fending off the hands of those who have paid, telling them they are here “just to dance”, keeping them away from sex. In a different space on the same stage, some play billiards with the locals, exaggerating how they play to accentuate the curves of their bodies.

The owner of the place, a fifty-year old woman originally from the southern Mexican border lets us look around and speak with the dancers in their dressing rooms. She insists: in this nightclub there is no sex trade “here we just sell fantasies.”

“Many men only want to see them undress, dance with them. Mostly they speak with the catrachas (Hondurans) because they say they are the prettiest. But we also have dancers from Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua. Most don’t even have sex. They just want to spend some time distracted from their daily lives.”

For sex, she says, other places exist.

I go to stage rear. Pinned to the door of the room filled with mirrors where the women arrange themselves are the house rules: how many times one has to dance and strip on stage; the number of beers the women need to drink with the punters (200 per week minimum). This activity is called fichar (literally, to sign up). The owner argues from each “sign up” or beer, half of the earnings goes to the women.

Inside the dressing rooms the fantasy for sale outside crumbles. Before going on stage Melani rushes down some beef soup and a soft drink. She says that she has not eaten all day because she’s having problems with her partner, who is jealous of her. And because he doesn’t get along well with her kids, all of whom are under eighteen.

She is 23 and she has three children. She says that she had to leave her country in 2009 because of “problems” with her previous partner. “He got involved with the Maras and well, you know, there’s a lot of violence in my country… I had to leave.” Melani left her children with her mother for a while. But when she got established in Tapachula, she brought them to live with her.

Her front teeth look decayed. She has visible scars on her calves, some of them recent. When she sees me notice them she pulls on her skin color Lycra, and on top of that she puts the clothes she will take off, piece by piece, on stage.

“He hits me because he is jealous of the clients who look at me. (He worked for a spell as a barman in the nightclub where she works.) But this is how I support my kids, how I support him. What does he want? That I work depending on a shop? They don’t even give us jobs in shops because they say we steal. And when they do give us jobs in stores the pay is miserable. I said to him, you hooked up with a Honduran. This is the life of a Honduran woman. It’s just that there they treat us well and pay us better.”

Everyday Melani confronts the stigma of being a “catracha”, a pejorative term tagged to the women who come from her country, who are seen as expert lovers. Her physique gives her away – broad hips, long legs, svelte waist – and does not let her fade into the background. “If I get into a taxi, the driver wants to grab my legs. If I work in a store, the owner wants to mess with me,” she laments.

In the dressing room’s neon light, the dancers put on their make-up, their long wigs, struggle into Lycra and clothes adjusted for cellulitis, a fat stomach, scars and stretch marks left by motherhood. Once on stage, its semi-darkness helps them.

Luis Rey García Villagrán, activist and defender of the rights of sex workers, confirms that in Tapachula alone – the largest city of the border region known as the Soconusco – there are more than 15 tolerance zones and around 200 centers where they can practice prostitution openly and in private: voluntarily or through networks of people involved in sexual exploitation.

Villagrán represents the Centro de Dignificación Humana and he thinks that this activity is taking place with the permission of society and government. “Here in this region any 5 year old child has seen that in front of her house, at her school, on her daily walk that there’s a snack joint, a bar, a brothel and a cabaret. I have seen Central American women enter and leave these places. This situation has become natural and has enslaved women in this activity.

Migrant women have become part of daily life in Soconusco. The population lives with them. Locals, including public servants visit the places where they work. As to their migratory status, they are only asked about it when there is an attempt to extort them.

Stigma Number Three: The Women Who Will Do Anything

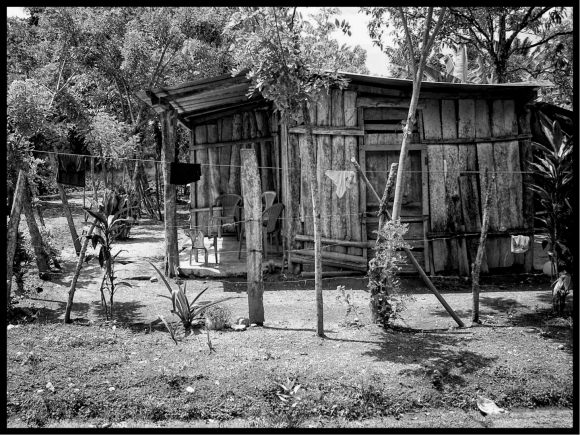

Aidé runs a rooming house located 10 streets from the center of Tapachula. This means she charges rent or lets out rooms with a plastic roof for those who request her services. Most of the residents are migrants without legal status in Mexico.

On arriving at the meeting with Aidé, I bump into a dozen migrants and their guide who are stuffed into one of the rooms. She is not intimidated. She says the migrants will leave the place in one or two days. Someone will come to pick them up so they can continue on their way.

She has been in jail accused of trafficking in people for the purposes of sexual exploitation. After three years inside she managed to get out.

“I had just been deported from the United States and I needed to continue sending money to my two kids who were still in El Salvador. A friend contracted me to manage a bar. The place wasn’t mine and the only thing I saw was that the servers did not get their money. If the girls want to mess with the clients in the rooms that’s their problem. It’s their way of earning a living. Nobody forces them.”

Aidé – instead of the bar’s owner – was arrested during a crackdown. Some of the women working in this bar located in Ciudad Hidalgo were minors. However, after a few days they were deported to their country of origin and nobody faced criminal charges for people trafficking. That’s how Aidé regained her freedom.

“When I got out I tried to cross to the United States again. But I couldn’t. They returned me again and that’s where you find me now, trapped in this place, without the power to move forward and without the power to return to my country,” she narrates with a grim countenance and brusque gestures that contrast against her clear, lovable eyes, her curly hair and petite figure.

A table, two chairs, an individual bed and a booming television sat on a little piece of furniture barely fit in the room. A 10-year old child does not take her eyes off the television. She is the daughter of a friend who is staying with her while she is looking for somewhere to live.

“I am resigned to living here in Tapachula or in Cacahoatán or whatever’s nearby. It’s all the same. But working as what? Here, Salvadorans can’t work as domestics because the woman thinks we are going to steal her husband. We look for work as employees and the boss wants to mess with us. In the bars they think we are going to rob or kill the clients,” she says while she readies a small case filled with varnishes and instruments to do nails, a service she provides at home and also at a small beauty salon in the area. She thinks this job is one of the few she can do where they don’t discriminate.

The migrant women who live in southern Mexico live lives trapped between a physical frontier that stops them from moving freely and a real border produced by discrimination, abuse, and social stigma that erases them as people.

Text: Ángeles Mariscal, for Periodistas de A Pie

I am an independent journalist, founder of the Chiapas Paralelo website. I contribute to CNN México and El Financiero. I run the Colegio de Comunicadores y Periodistas de Chiapas (CCOPECH). To have the conditions necessary for a dignified life in the places we come from is a right, and to migrate when they don’t exist is also a right. It’s from that perspective that I cover the subject of migration.

Images: Moysés Zuñiga Santiago, for Periodistas de a Píe

A photojournalist from Chiapas interested in the struggle of indigenous communities and migration across Mexico’s southern border. I work with La Jornada, AP, Reuters and AFP. My work has been shown in New York University in 2010 and 2013. I traveled with young people like myself crossing the border in search of opportunity, taking personal stories with me that let me journey beside them. I do this work because of that; I want to make extreme situations of violence visible so that these situations don’t occur and people don’t die.

Translation: Patrick Timmons, for the Mexican Journalism Translation Project.

Translator Patrick Timmons is a human rights investigator and journalist. He edits the Mexican Journalism Translation Project (MxJTP), a quality selection of Spanish-language journalism about Latin America rendered into English. Follow him on Twitter @patricktimmons. The MxJTP has a Facebook page: like it, here.