Madera, Chihuahua: A Land Living through War

Marco Antonio López (La Silla Rota)

Las Varas, Chihuahua has a population of 1,417. It is the site of brutal confrontations between two warring drug cartels.

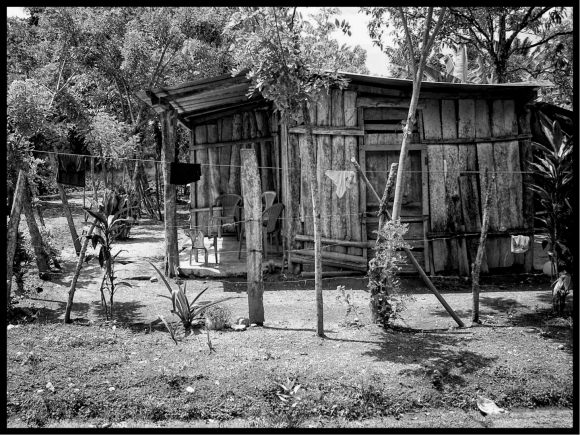

Las Varas, Chihuahua is a town where nobody knows who is in control nor what rules apply. To survive people know what it takes to stay safe after six in the evening. Survival is what they think about when they use the highways crossing Chihuahua’s western mountain range.

Las Varas, with its population of 1,417 people, is where two drug cartels fight over territory, according to the explanation from the Office of the State Attorney General in the Western District. La Línea of Ciudad Juárez and the Sinaloa Cartel have let loose war in Chihuahua’s mountains, submerging the western part of the state in a violent dynamic, severely impacting the region’s tiny population. Death, shootouts, kidnappings and disappearances have become routine, daily events.

Those in control for now are the state, federal and military security forces. They arrived this Wednesday after a confrontation between both criminal groups leaving fifteen dead and wounding five people. But the second in command of the Chihuahua State Police, Alberto Chávez also says that once they leave the area will be unprotected, at the drug traffickers’ mercy.

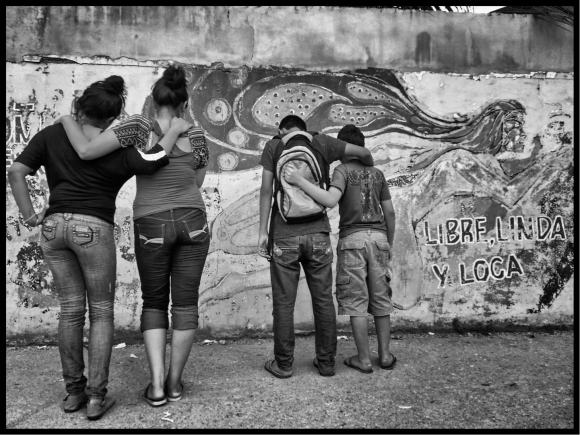

So the police do not have permanent control. Nor do La Línea or the Sinaloa Cartel. The mountains are the land everybody wants and nobody has. The paradox is that the people who have least control are the ones who live there.

At the town’s entrance there is a sign that says, “Las Varas.” The rectangular metal bearing these letters has holes in it from at least a dozen heavy caliber bullets. Next to the sign there is a cemetery, and in it lie the dead with their rights to a name, remembrance, and Christian burial. The entrance to the cemetery is littered with spent shell casings, its gate shot up more than a hundred times. A bullet-ridden cross serves as a warning against poking around.

Two improvised bunkers sit right there by the main entrance. The hideouts are littered with cartridge boxes, two mattresses, food, cans, and bottles of beer. The police here said that they belonged to La Línea.

Behind the cemetery is a place set aside for those dead who, somebody decided, don’t deserve a cross with their name. Without a marked grave family do not know where to stop by with flowers from time to time. Five graves were found right there: a total of seven bodies in a state of decomposition. A mess of bones. All of the dead bodies were mutilated and two were decapitated. Untended graves. Nobody is looking any deeper into things. Although the second in command says that there are permanent traces of what happened, there are no investigators because they are all occupied elsewhere, collecting cadavers or identifying unnamed bodies.

Further into town there is a warehouse, the scene of a brutal massacre. Outside, shot up doors and walls. Inside there are bloody pools and blood spatters, macabre decorations left by merciless killers. Right here the lifeless bodies of those fifteen men and the five left alive but wounded were gathered up and taken to Chihuahua. The prosecutor says that the confrontation between the two criminal groups began around six o’clock on Wednesday morning, lasting about an hour, with security forces arriving afterwards. However, an official said that where you see a blood stain on the wall, that’s where an injured man was resting when somebody else found him and shot him in the head. His brains were spattered across the wall. The official version is dubious if not kind of tactless. “That’s where that pig was,” he says under his breath.

There are stretches of blood on the warehouse floor. They are black, that color blood makes when it dries. They are run through with the marks of truck tires trying to getaway. Nine vehicles – one of them armored – were seized there, along with long arms and fragmentation grenades. By midday Thursday what remained were bags of corn, potatoes, tomatoes and other food along with cushions, casings, bullets, bags, clothes, and marijuana. Everything behind a metal door bearing a stenciled sign: “Failing to make time for God means living is a waste of time.” It too is shot up.

The cemetery and the graves are by the town’s eastern exit, the one that leaves for the state capital. The warehouse with its massacre and its remains are to the south, towards Madera. The municipal building is in the town center. It is closed. Nobody came to work. There is a little building, barely the size of a room right beside the municipal building, its front wall riddled with holes left by large caliber bullets. The windows are all shattered. A burnt out truck sits right by the door. The room was a command post. Last week an armed group ambushed two state police officers, murdered without anybody able to stop the brutal attack.

In less than a month, eight bodies turned up, two police officers were murdered and fifteen suspected drug traffickers were killed. All of it happened in Las Varas. One person, who would only speak on the condition of anonymity, said the graveyard was shot up because it was the site of another battle leaving as many or more dead from the warehouse fight. But no police turned up and each group carried off their own dead. These facts, however, do shock: at least twenty-four people were killed in the last month. Most of those buried bodies are just bones in several graves. The town has fewer than 1,500 residents.

The person who told the story about the graveyard said armed men who are not police have placed roadblocks on the highways. These men ask about where you are going and your purpose. They decide if you can continue on or not. They can take whatever they want from you, including your car. “That’s why I have this cellphone,” the man says, before proceeding to say how they took his other one on the highway from Madera to Las Varas.

The countryside is impressive and overbearing. Las Varas is one of 42 communal land holdings (ejidos) in the municipality of Madera. It’s the town that provides access to deep into the mountain range. It has a waterfall, a scenic overlook, rivers, swim parks, archaeological zones. All this beauty makes Las Varas magical. On sight paradise springs to mind. But these are abstract notions and the facts overwhelm instead. Violence has made this place into something quite different: a town with and without law in the service of drug cartels.

The natural beauty that makes Madera attractive is also its principal problem. Situated on the highway that wends into the mountain range, it has become a strategic point for drug trafficking. That’s why factions within the two cartels fight over this place, says Félix González spokesperson for the Western District of the Chihuahua Attorney General’s office.

The problem became so big that the municipal police, with its 100 officers and less than forty patrol cars became overwhelmed. State authorities entered into an agreement with the town, assuming control over security since 18 February. But violence is still on the rise. “Unfortunately, these things that cannot be avoided. It is a war between them. It’s like a family feud,” observes second in command Alberto Chávez Mendoza.

Of the fifteen killed in the shootout, five have been identified. They came from towns in Chihuahua. The youngest of them, Luis Leonel C., was 18 years old. Rafael C. was 25. Hugo Antonio G. was 33, Álvaro T., 35, and Astolfo C., 47. They spent their last day alive surrounded by the terror guns cause when aimed to kill.

The five wounded men were arrested. Only one of the wounded comes from Chihuahua, Leonardo G., who is 18 years old. Carlos H., 24, was born in Hidalgo. Efraīn G., 25, is from Michoacán. Marco Anotnio M., 27, comes from Tabasco. And Luis G., 36 years old, was born in Minatitlán.

A week ago, Chihuahua’s governor, Javier Corral announced a salary increase for state police officers, grants for their children and an increase in their life insurance policies. He committed himself to reducing violence in the state and of bringing calm to Chihuahua’s residents. The state attorney general, César Augusto Peniche, said the homicide rate was deceptive and that really security had improved.

The prosecutor’s office in the Western District impounded the shot-up trucks from the confrontation. One even has a bloody handprint on the bodywork.

A woman came out of the coroner’s office in tears. She had to identify a dead family member so that he could a have a name and a grave with a cross on it to visit from time to time.

A convoy of about thirty squad cars with more than sixty state police and prosecutor’s officers patrol the highway that winds into the Chihuahuan mountains. Soldiers on the lookout for criminals. Two helicopters soar above the immense pines. A commander says that they are about to leave and that the cartels will continue their fight over the region. In this battle the one with more kills wins.

Journalist Marco Antonio López Romero writes for La Silla Rota. He is based in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua.

Translator Patrick Timmons is a human rights investigator and freelance journalist based in Mexico City. He edits the Mexican Journalism Translation Project.