This article was first published in El Diario de Juárez on 14 February 2005. It has been translated without permission by the Mexican Journalism Translation Project (MxJTP). There is no web-accessible version of the Spanish-language original.

This translation is dedicated to the work of journalist Sandra Rodríguez Nieto.

Translator’s Note: Armando Rodríguez Carreón, “El Choco,” was a veteran crime reporter for El Diario de Juárez until his violent murder in November 2008. You can read a portrait of El Choco by his colleague Martín Orquiz for Nuestra Aparente Rendición, here (unofficially translated into English for the MxJTP).

Rodríguez’s murder continues in impunity, with multiple failures in the investigation. El Choco’s unsolved case is one that marks Mexico as infamous for its inability, or unwillingness, to get to the bottom of journalists’ murders, meaning that it ranks number 7 on the Committee to Protect Journalists’ Impunity Index for 2014. In the Inter-American System of Human Rights, and pursuant to Mexico’s 1998 ratification of the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR), the state has the international responsibility to investigate, prosecute, and punish human rights abuses, and provide reparations: among other human rights violations, Armando Rodríguez and his family have been denied access to justice for his murder, implying the state’s violation of a human rights treaty, the ACHR.

The MxJTP has translated this 2005 story by Rodríguez because the stories that place Mexico’s hard-hitting journalists at risk are themselves in danger of being forgotten. So, the act of translation can also be an act of recuperating the memory of the work of a slain journalist.

But on its own terms, Rodríguez’s February 2005 article is distinctive because it discusses different ways to count the violence along the U.S.-Mexico border, excavates the history of the city’s violence — a historical issue that he identifies as ever present but has changed over time — and because Rodríguez used sociological analysis to identify with a great degree of prescience Juárez’s oncoming descent into violence. This murderousness would, ultimately, consume him, too.

Even today, the Mexican government still disputes murder statistics and is still unable to reduce the country’s impunity rating. And, even though Rodríguez identified structural issues common to modernity that contributed to the rise in violence, less astute and overly descriptive commentators and analysts have sought only to explain violence in Mexico and specifically in Juárez through the lens of drug trafficking.

Specifically in regards Rodríguez’s murder, we still don’t know why he died or who killed him. But that shouldn’t mean that we ignore what he bequeathed us, his willingness to inform society of important events by writing journalism. PT.

A Voice from the Grave: Juárez, the Border’s Second Murder City

by Armando Rodríguez (EL DIARIO DE JUÁREZ)

SIDEBAR — MAIN STORY FOLLOWS…

– An investigation by El Diario, based on data from the Attorney General of the State of Baja California Norte, shows that of northern Mexico’s fourteen most important border cities, murders are most numerous in Tijuana: 705 cases from January 2003 to December 2004.

– Juárez took second place with 402 murders for the same period, approximately 17 murders per month.

– The study contrasts these figures with the number of murders during the same period in San Diego, California (127), while in El Paso there were just 33.

– The report notes that murders in Tamaulipas’s cities are less numerous than those of Juárez or Tijuana.

– Ciudad Juárez ranks second in northern Mexico’s border region in terms of violent homicides in the last two years.

– The cities with a low murder rate are: Nogales, Arizona, with just one murder in two years; Calexico, California, with two cases; and Hidalgo, Texas without a single murder over the same period.

– The Tamaulipas Government’s website (www.procutamps.gob.mx/portales/estadistica.asp) indicates that from January 2003 to October 2004, Nuevo Laredo registers 120 murders, 74 in Reynosa, and 65 in Matamoros.

– The president of the Center for Border Studies and the Promotion of Human Rights (CEFPRODHAC), Arturo Solís Gómez counts 189 homicides during 2004 in Tamaulipas’s border cities. And 70 of these can be tied to drug trafficking, according to data published by internet-based sources.

– The figures for Tamaulipas are still below those of Juárez and of Tijuana.

– The data clearly indicates that the Mexican side of the border is more violent than the U.S. side in every single case.

Crime and Society

Juárez is considered Mexico’s twelfth most unsafe city, according to the Fund for Public Security in Mexico’s States (FASP).

This ranking can be compared with the assessment made by the Federal Government’s Ministry of Social Development (SEDESOL). The Ministry says that the border is the most violent area of the Republic.

The three cities in the country most overtaken by insecurity in proportion to their population size are: Juárez, San Luis Potosí and Acapulco. The report is currently [for 2005] being distributed on the webpage of Mexico City’s Attorney General: http://www.pgjdf.gob.mx/violencia.asp.

The SEDESOL report indicates that these three cities rank high in terms of murders, rapes, violent events, and suicides. When these violent events are added together, it means that cities can be compared against one another in terms of violence.

But the international business magazine, América Economia, suggests that the homicide index in Ciudad Juárez has registered a fall of 41.5 per cent over the last four years.

The magazine’s study, which was undertaken for business interests, declares that in 2001 there were 26 homicides per 100,000 residents, while in 2004 there were 15.2 homicides per 100,000 residents.

Ciudad Juárez’s murder statistics, compiled from the state district attorney’s autopsy records and compared with El Diario’s review of that data, demonstrate that in thirteen years there have been 2,957 violent homicides.

The crime figures have become more significant after the U.S. alerted its citizens to the wave of violence in Mexico’s border cities.

In Juárez, U.S. Ambassador Tony Garza said that insecurity in Mexico’s border region is a result of drug trafficking.

“We know very well that in certain cities there are growing tendencies for criminal activities, in some more than others, but the alert was for the length of the border and not just for one city,” he noted.

“I believe that Juárez is not one of the most violent cities in the Mexican Republic. The thing is that it has a bad reputation because of the deaths of women. Monterrey, Guadalajara, and Tijuana have more murders,” said Assistant District Attorney Flor Mireya Aguilar Casas.

She indicated that in spite of border cities’ problems with a floating population, statistically there’s evidence that they aren’t more dangerous nor are more bloody acts committed here.

“I don’t think it’s risky for a foreigner to come visit this city and I don’t think that there should be an imminent danger alert for these cities,” she added.

The Most Violent Year

Paso del Norte was established in 1659 and even before it was called Ciudad Juárez, in 1888 it had been struck by violence, a result of social movements leaving death in their wake and that have marked the city for life.

Historian and journalist Davíd Pérez López says in just a few days, in December 1846, there were 80 deaths on the Mexican side of the border, a consequence of the war against the United States, whose army had invaded Mexican territory.

When Ciudad Juárez was “seized” in 1911, he notes that 75 federal soldiers were murdered and 102 wounded, while among Madero’s supporters there were 160 deaths and 210 injured.

“There were other low points in wartime actions in Ciudad Juárez, like when Orozco’s supporters arrived in the city. Orozco had rebelled against Madero, and Villa fought against him: forty people died. That was in 1912,” Pérez López said.

Also in 1921, there was another social uprising in this region, known as Escobar’s Rebellion, totaling twenty violent deaths.

But in Ciudad Juárez’s recent history, and without there being a war, 1995 was the city’s year of violent deaths.

Coroner Enrique Silva Pérez said that during the ’80s, ten to twelve homicides started to happen each month.

But the medical specialist repeated that 1995 was Juárez’s most violent year. “I remember that in February ’94 we had eight murders. In February ’93 there were 6, but in February ’95 we had 34 murders,” he said. When the year ended, he noted that 294 people had been violently murdered.

In the country’s south, people get killed with machetes. It’s an overwhelming feature. But on the northern border, especially in Ciudad Juárez, murders happen with firearms, he said.

Ways to Die

When Dr. Silva Pérez began working in the ‘80s at the Coroner’s Office of Chihuahua’s Assistant District Attorney, violent murders numbered fewer than in recent years.

“Usually the cause of death was from a knife, from punches, or from firearm wounds,” the professional confirmed.

At the end of the ‘80s and the beginning of the ‘90s, gunshot murders increased and took first place as cause of death, responsible for about 60 or 70 percent of the total number of homicides.

At the same time, knife murders decreased, but in 1993 a new way to kill emerged: strangling murders or death by asphyxiation, principally crimes against women and executions related to organized crime, Dr. Silva Pérez added.

“The extreme violence began precisely with drug-related murders. Strangling is the cruelest way of dying because the victim suffers more.”

Silva Pérez indicated that gunshots have caused death but there are also postmortem lesions, like stab wounds, indicating extreme violence.

One of the most brutal cases the coroner remembers from his 24 years of work in the forensic service is of a couple and their baby who where murdered and then dismembered.

“There have been other similar cases, but the way they dismembered this woman showed that the person who did it was her lover,” he said.

In other cases, the victimizers tried to make their victims disappear, so they burned them. But careful, scientific work can show that the person did not die from being incinerated, he explained.

High-powered arms also destroy bodies.

“I’ve had to deal with cases of former police officers who were murdered by assault rifles. When we did the autopsy we could determine more than 70 wounds from high caliber bullets destroying the body, turning it into shreds,” he said.

The Causes of Crime

“Why did you do it?” the reporter asked a man who a day before had shot a sixty-year old car tire repairman from Salvárcar.

“Craziness,” Nicolás Frías Salas said, with a still uneasy look produced by alcohol and drugs.

For the Assistant District Attorney in the Northern Zone, Flor Mireya Aguilar Casas, the consumption of drugs and alcohol predominate as causal factors in violent homicides.

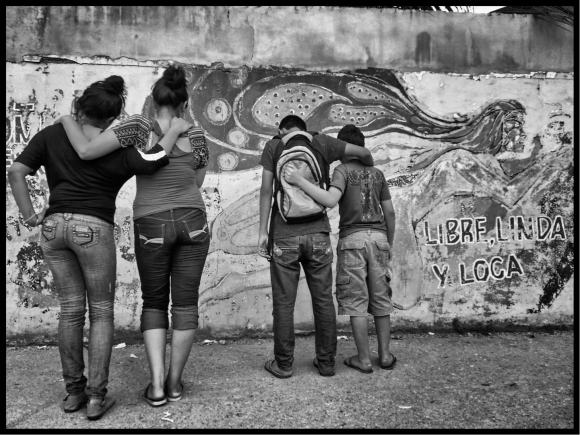

Another factor influencing murders in Ciudad Juárez is familial disintegration, decay, or the decline of values – social, religious, cultural — inherent in human beings, she said.

“Gangs are another social problem that cause crimes, along with economic questions, extreme poverty and lack of work.”

The Assistant District Attorney confirmed that Ciudad Juárez has a high index of gang-related intentional murders.

“In criminal cases, gang members committed the majority of homicides currently in judicial proceedings,” she said.

She does not believe that impunity encourages crime: “whoever commits violent murder does not believe that their behavior will go unpunished, although that might be the case in a minority of cases.” [Translator’s Note: former El Diario reporter Sandra Rodríguez Nieto’s study of an interfamilial killing in Ciudad Juárez, La fábrica del crimen (Planeta, 2012) contradicts and disproves the Assistant District Attorney’s general contention. PT]

A Sick Society

For the sociologist from the Autonomous University of Ciudad Juárez (UACJ), chaired professor Alonso Herrera Robles, homicides can be seen as part of a social pathology (sickness or abnormality) and affect industrial society’s like Ciudad Juárez.

This type of collective group, one that is entering modernity, may be labeled an at-risk-society, he added.

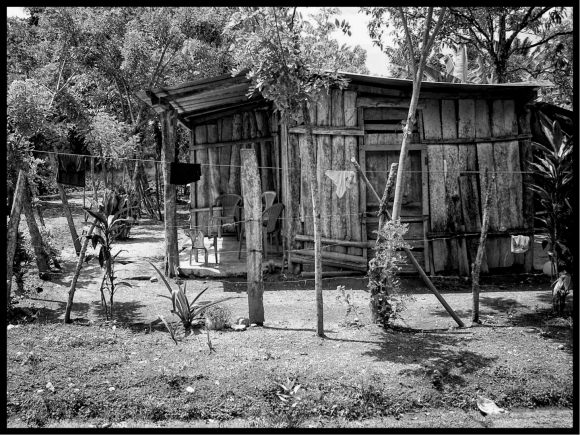

He mentioned that Juárez, thanks to the arrival of the maquiladora industry in the mid-1960s, experienced a series of structural changes. And the massive incorporation of female labor in the production process was one of those overwhelming characteristics.

“It changed all the structures and the social organization of production and impacted society,” Herrera said.

The director of public safety for the city, Juan Salgado Vázquez, agreed: “Juárez has grown at a giant’s pace, and this growth has had an important bearing on criminal activity.”

“The city has grown faster than the capacity to plan, to build, to construct a safe environment for its inhabitants. The problem is not just with security but with its infrastructure and all of its services,” he stated.

“The city’s growth has overtaken out capacity to respond,” he said.

Added to growth issues, the city has a large number of families, whose men and women have been working for thirty years. We haven’t found a way to raise their children. This means that there are more people disposed to commit crimes, he suggested.

He said that one of the solutions to the problem is that there needs to be greater participation from civil society. Other solutions might be found in reforms or legal mechanisms to protect vulnerable groups, like children, the elderly, women, and indigenous people.

“The problem is now that violent murders aren’t dealt with either by the authorities or by civil society. So what’s happening is that these acts of violence are becoming part of our daily life and making the culture one of violence,” he expressed.

“This is going to become cultural, it’s going to become part of daily life, just like what has happened in other cities with protracted wars, like in some Colombian cities.”

For the professor, the presence of more police officers in the city is just palliative. There can be more police but this does not mean they are better organized.

“The social costs of this progress, or of technical advances and development, are reflected in pathologies like homicide, and it appears as a by-product,” he warned.

Some writers have called this phenomenon, “modernity’s perverse consequences,” he said.

Journalist Armando Rodríguez reported for El Diario until his murder on 13 November 2008. This article first appeared bearing the title, “Es Juárez la segunda frontera en homicidios.” It is not available on the Internet.

Translator Patrick Timmons is a human rights investigator and journalist. He edits the Mexican Journalism Translation Project (MxJTP), a quality selection of Spanish-language journalism about Latin America rendered into English. Follow him on Twitter @patricktimmons.