Fire Destroys the La Terminal School

This article was first published in Guatemala’s Plaza Pública on 4 April 2014. It has been translated without permission for the Mexican Journalism Translation Project (MxJTP). Financial support for the translation of this article comes from an anonymous donor and is gratefully received.

At the Bus Terminal: Meet Guatemala’s Child Workers Struggling to Study

By Oswaldo J. Hernández (Plaza Pública, Guatemala)

One of the three schools operating in the bus terminal’s market disappeared when a fire destroyed a large part of the structure during the last week of March. (Translator’s Note: the bus terminal is known simply as, “La Terminal” PT.)

The educational center attended by 40 school age children was part of the Educational Program for Working Adolescent Boys and Girls (PENNAT). Getting an education there has always been different. It’s part of another reality. But something behind the burned out school remains: an educational system that operates on the sidelines of state coverage. This schooling provides a portrait of working children in Guatemala’s largest market. Those marginalized children who cannot get an education any other way.

In Guatemala’s largest market, an almost invisible scene repeats itself every morning, Monday through Friday. There are the usual comings and goings of buses and cargo. The selling, the cries, smoke, eateries, improvised stands, liquor, bars — the rush of it all, the places that sell meat, vegetables, grains and fruit. And right there, in that uproar, about 150 children – some of them vendors’ children, others of scarce resources, but mostly all workers – walk the aisles towards three different places inside La Terminal’s market (El Granero, La Tomatera, y El Techado). The Grain Aisle, the Tomato Aisle, and the Covered Section. These are also the children who steer themselves early in the morning towards studying in makeshift schools that operate in the innards of La Terminal.

These children cast silhouettes between the market stalls along this route. Just more among many. Small, invisible – until each one enters their classroom. At that moment they seem to say “we exist,” “we are here,” leaving behind for an instant the mass of more than ten thousand people who pass through each day.

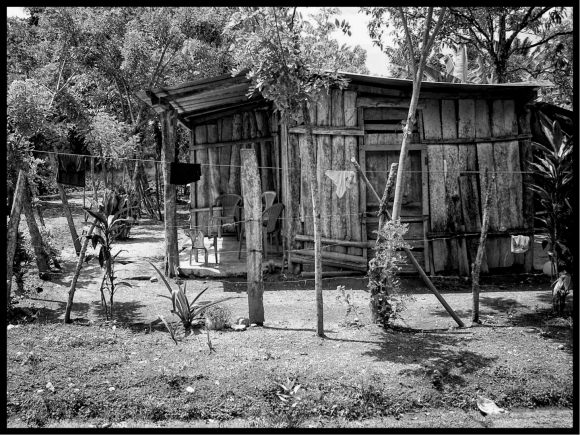

Children attend school for two hours a day. This is the school before the fire destroyed it.

Fifteen-year old Catalina trod that path on the morning of 25 March 2014. As is her custom she wends – small and invisible – through the terminal. She does this every day, losing herself in the throng to finally arrive at her class for study in the fifth and sixth grade of primary school. She’s taking the two grades at the same time, the last stage before graduating from primary school in the PENNAT program. After she finishes her day, she buys fruits and vegetables in the market and in the afternoon returns home to work in another market in Zone 1. But this morning, when she arrived at the bus station, she couldn’t get in. “When I arrived, I saw the smoke, the firemen, and the market in flames. The first thing I thought about was my little school,” she says, a day later.

The Terminal’s covered market had burned, almost in its entirety. Inside, between the stalls on the second level, was the classroom attended by forty child workers from PENNAT. It was a small space. Every day the first task was to make a drawing. Each child expressed his or her feelings. Weeks before the fire pictures on the walls in Catalina’s classroom read, “I am happy,” “Today I feel happy,” “I feel sad,” and “I haven’t eaten.”

Self-esteem is important for the child’s development. Most say they feel happy, but a couple say they are sad.

Daniela is the only girl in her class in the covered market who comes to school in a uniform. She had written on the wall that morning: “I feel happy.” She also said that in spite of the fact that La Terminal’s school doesn’t require a uniform, she wears it so that “she doesn’t lose the custom.” According to her friends, María, Heidy, and Flory, Daniela has been in an orphanage where “they hit her.” Daniela, fourteen years old, is at the PENNAT school to finish fifth grade. “My grandmother works close. She says that I must study. We went to a school but they told me that since I was fourteen, I couldn’t enter at the right grade level. We never thought that if I grew up I would be left behind. But they wouldn’t take me. So they told my aunt about a school in La Terminal, and here I am, studying.”

La Terminal’s fire last 25 March destroyed Daniela’s classroom. Flames consumed one of the three PENNAT schools operating in La Terminal. Officials calculated the loss at some 80,000 Quetzales (US$10,000). Teachers in the program issued a press release asking for help: “We need to replace 40 triangular desks, 40 chairs, 3 bookshelves, 20 computers…” La Terminals is where they also have to provide computing classes to the 150 that still study inside the market. “We still have to pick ourselves up, to dust off the ashes,” says Lenina García, PENNAT director. “The children that lost their classroom have to study temporarily in our other two classrooms, in El Granero and in El Tomatera, while we begin to recover.”

In public schools, children older than ten are considered too old for primary school.

The school here has never been like a conventional school. The primary school inside the market is split into three phases each with two grades (first/second, third/fourth, fifth/six) with each phase taking one year. A child that attends the Terminal school graduates from primary in three years. In the first two phases, each child attends only two hours of school a day. The third phase of primary requires four hours a day. But the students are the school’s most important element: children who work; children who have not been able to continue their studies because the official education system has rejected them because they exceed the age limit for each grade; children with a different reality. It bears repeating that to study inside La Terminal is different from what happens in other primary schools in Guatemala, in schools that have their own buildings, with classrooms, with a central courtyard, where children wear uniforms and spend five hours a day on average in school, inside a classroom.

In this market, this gigantic center of business, some crucial factors make studying fundamentally different. “They are children who help their families. Poverty doesn’t give them any other option. Most get up before dawn, and from the early morning they are selling or helping out in some stall or other. They work. They help. For such reasons they don’t succeed in finishing official grade school, and out of necessity, many of them are obliged to abandon their studies completely,” explains García, while walking between the market’s aisles.

The smallest child goes to school. Resources for education are minimal but the enthusiasm of teachers and students is immense.

PENNAT is responsible for the educational programs in La Terminal. Similar projects exist in another seven markets in Guatemala: the Central Market in Zone 1; the San Martín Market in Zone 6; the Guarda Market in Zone 11; the Educational Center in San Pedro Sacatepéquez, zone 4; and in zone 1, the Mixco Educational Center; the San José Pinula Educational Center, and the Alliance with the Children’s Shelter (Lazos de Amor and Amor Sin Fronteras educational centers).

Around four thousand children work and live in La Terminal, according to its financial backers Save the Children and the German non-governmental organization THD. There are 150 children attending their three schools. In 2014 they hope to serve 600 children.

When age is the obstacle

After the fire, one of the schools that Daniela and Catalina will study in temporarily is the Granero. Around it there are hundreds of banana and grain stalls, as well as a charcoal seller. It’s hot under the damaged five-meter high zinc ceiling. The Granero is really a type of giant warehouse. Its inside is suitable for hundreds of divisions, fragments, spaces that form cement and wood stalls. The school operates there in a space of fifteen square meters.

A girl’s snack: tortillas with sausage.

It’s morning. Some twenty children between seven and thirteen years old make circles with their work tables, shaping homemade Play dough, made with flour, water, oil, and powdered drink mix. Trapped under a thick fug and dirty surrounds, they are studying for the first and secondary grades of primary school; two grades at a time. That’s how the educational system works in La Terminal.

It’s weeks before the fire at La Terminal and the Granero children are concentrating. Nine-year old Hector explains that he spent more than two years trying to study first grade in a school in zone 18. “I stated at six, but I wasn’t progressing,” he says. His grandmother, Corina de la Cruz, a house cleaner, says that one day the teacher at the official school didn’t want to accept him, explaining that he had exceeded the ideal age to write and read, that he wasn’t managing to focus and wasn’t retaining information. That was the end of it. The school viewed him as a lost cause. They ended his educational career. They would no longer accept him. At the very moment when his grandmother was speaking, Hector read some paragraphs from an advertising leaflet. “He is learning here,” says his beaming grandmother, one hand palming her grandson’s head.

Sindi Paola, thirteen, comes up to show off a drawing. “A drawing,” she says enthusiastically and holds out a notebook covered in dust. She has formed the letter B with small balls of paper stuck down with white glue. In a delicate doodle, she has drawn a boot to show how to vocalize the sound, the form of the letter. There’s the drawing. At thirteen years old, this is the first year of her life in which Sindi Paola is in the first year of grade school. “I work. I clean tables. I help to pay for the room where my parents and my brothers live.” Then she goes on, taking a breath, “I want to learn to read.”

Sindi Paola: “I work. I clean tables. I help to pay for the room where my parents and my brothers live.” And she studies: “I want to learn to read.”

The schools in La Terminal run by PENNAT started eighteen years ago. “A group of education students, among them Professor Jairo González, went from stall to stall, teaching the sellers’ children to read and write. It was 1995,” says Lenina García. Since then the Education Ministry (MINEDUC), through the General Director of Extra-Curricular Education (DIGEEX), certifies the accelerated primary to provide education.

The content of the course books is based on the everyday lives of the children.

The textbooks have been adapted to the reality of La Terminal’s working children.

“The reality for the children of this place is distinct and, in a certain way, incompatible with the official education program,” says García. “That’s why PENNAT started, an option close to the context of the market: an alternative education for boys, girls, and adolescents who, because of their economic condition have to work to survive. The most urgent consideration is that children must not abandon school. When they work, they don’t complete school grades, they get older and bit-by-bit the system excludes them. They can’t read or write. Left without opportunities,” she explains.

The Ministry of Education says a few weeks later that the ideal age to complete each grade of primary school does not rest on one factor. There’s nobody to give a reason to say this or that child is barred from admission because of age. However, teachers employ criteria that mean it is difficult to teach a child when they are older than their classmates. That’s what Patricia Rubio outlines. She’s DIGEEX’s current director – the entity that supports market-based education, even though it’s not a part of the state. “It is important to understand that DIGEEX does not assist children,” she says up front. “DIGEEX works with those who are too old for regular schooling. We mostly help adults. Our programs – Correspondence-based Education for Adults (PEAC) and Family Educational Centers for Development (NUFED) – are focused on people that have been excluded – because of poverty, displacement – and this situation challenges their studies. We help after the age of thirteen,” Rubio says.

The state does not have any options when it comes to avoiding children falling behind when they are over thirteen years old. In fact, the Ministry of Education waits until that age to help them, providing assistance programs through an accelerated primary that attempts to help them move forward. Adults attend, as do some adolescents. The DIGEEX offers primary in two phases: all of primary school in two years, but a very young child, lagging behind, and not yet 13 years old, cannot attend.

“That’s our mandate. It’s that way to avoid fighting with the regular school framework that covers ages from six to twelve years old,” maintains Rubio.

Meanwhile, hundreds of children from nine to twelve years remain in limbo in those cases where the teacher applies the criteria, or, when a school that tells them that “they are sorry,” that they excuse them,” “they forgive them,” but that they can’t finish first grade if they are already “too old.”

She is the oldest. She takes care of her two brothers while her parents work. The boys go with her to school.

That was Hector’s case: after being rejected by the official system, he began studying in the Terminal in the PENNAT school. In practice, it was the only option left to him. That was when nobody was betting on his future. Rubio added that in spite of age, schools are obliged to provide primary education but it’s recognized that there are few teachers who will support a child of ten or more years in their first grade classes. On first sight, they distort things. Statistical, ethical, and psychological distortions.

A System that Adds and Subtracts

Adding. The child workers of La Terminal learn to count before they go to school.

When was age linked to learning by grades? How did pedagogy establish exclusion from primary school for a child who exceeds a grade level by two years? How to understand the decision to establish such criteria?

Félix Alvarado, an education specialist, says that it is likely that the origins of age-linked primary grades, as with school-based education more generally, comes from industrial production in the first half of the nineteenth century. “They needed to learn just enough to start work in a factory at around age 10 or 12, if that’s what they were going to do.”

When school gets out, the children have to run home to deal with their reality: working to survive.

In DIGEEX they don’t offer a solid response. They admit that even though they have to help this population no criteria defining that population actually exists.

MINEDUC’s overage school rate (the percentage of students behind by two or more years according to their corresponding grade) implies that a number of students will chance their fate: at primary level, the figure for those children who exceed the age of their grade level has remained stable in recent years at around 22 percent. But in 2009, something strange happened in primary schools: the overage primary school population surged by more than half, to 51.69 percent.

Perseverance and commitment. Maybe they haven’t learned these words at school yet but every day these children already practice them.

Enrique Maldonado, an economist with the Central American Fiscal Studies Institute (ICEFI), has analyzed this sudden peak: “Primary school coverage increased, the number of children served grew, but that was the year in which conditional transfers began. The error of those programs was that there was no pedagogical strategy that differentiated between children in extreme poverty that had never been to school with those that normally went to school. Thus there was a distortion in the indicators of internal efficiency and more assistance to overage school children in primary school.” From that year on, there has been a mass desertion from primary school. “For 2009, in first grade of primary school enrollment was 624,359 children; 567,830 in 2010; 530,976 in 2011, and 480,039 in 2012, meaning that in four years the national education system expelled around 150,000 students, just in the first grade of primary school.”

— What are the general causes of overage schoolchildren?

— First, there are bad teachers in first grade. When a school gets a new teacher, without experience, from the moment of their entry the other teachers conspire to assign them to the first grade. And, second, the pre-primary coverage the state provides. In recent years, the state has failed to cover half of the children between four and six years old. Children enter the first grade of primary school without any preparation.

— Why did so many children drop out after conditional transfers?

— They did not find what they were looking for. The children didn’t find teachers who spoke their language, nor books in their language, nor utensils, nor desks, and even food and schools were scarce. One of the errors in implementing the conditional transfer program was to have first not strengthened public school supply, responds Maldonado.

After studying, she helps her mother sell used toys.

The primary and pre-school educational system gives the sense of a giant paradox of advances and setbacks: rate improvements followed by declines. A framework containing obstacles against school enrollment if a child is too old, and has to repeat a grade several times. Or it amasses dropouts in those cases where access diminishes at each education level. In 2009, primary coverage in Guatemala reached 98.7 percent; but in 2012, according to MINEDUC figures, it dropped to 85.1 percent. There are highs and lows: the children who abandon school, of still more exceeding school age; the intricacies of the system’s paradox; among the percentages; the rates of child work. And still PENNAT works in the markets. PENNAT takes on most of the excluded, the product of the advances and the setbacks.

Doing chores and distributing tortillas made and sold by his mother are some of the things he has to do when he leaves school.

The Child Worker

The Tomato Aisle is La Terminal’s area for bulk tomato sales and because of its age may be one of its most emblematic features. Resistance by its tomato sellers to any intervention by the city authority has been strong and ceaseless. They have organized themselves. It’s the most formal face of the informal economy. Battle hardened. Within the Tomato Aisle, however, the sellers have given space over to PENNAT. Usually it’s the sellers meeting room but from Monday to Friday it functions as a school. The school population has reached 60. It was one of the places that remained intact after the fire. Students begin the second phase there: third and fourth grade of primary.

At ten in the morning, the children sing a song. Their voices may be heard from outside. “When they come full of energy, we need to drain their batteries a little. We do that by singing,” says teacher Jenny Chocochic. Around her there are children that have bootblack on their hands. Others say they sell gum in the market. One girl sells atole. A boy helps his mother distribute tortillas throughout La Terminal’s aisles. Their ages range between nine and fourteen years old. “If there are more than two hours of school I wouldn’t have time to study,” says Mateo, who helps his family run a market stall. “I am going to finish fifth grade as quickly as I can,” he adds.

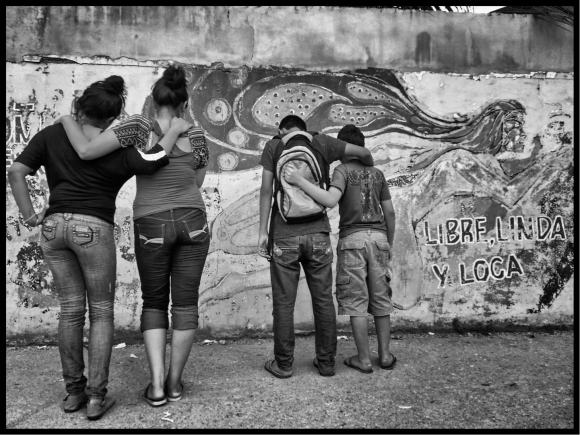

La Terminal’s children quickly turn into adults. Not because of biology, but because of their responsibilities, taken on at an early age. He’s a seller and he takes care of his sister.

Most work on the outskirts of the market, where they also sleep and study. Speaking with the children you understand the market is their world, their immediate universe. They have tough histories to share – of alcoholism, separated parents – families that have had to travel to the capital to rent a small room to survive. Overcrowding. “One day we saw a dead man,” says nine-year old Gerson, “he’d been shot. He was a thief. They shot him in the head.” Lucia and Jocelyn, seven and eight years old respectively, live nearby. The girls were abandoned by their mother in the house of their grandmother, María Gaspar. The sisters do their homework beside a bus and near the tortilla stall where they help their grandmother. “I take care of them like they were my daughters, my little girls,” Zacarías jokes, who stands behind them in the sun, drunk, and who says that he does whatever in the market. The girls eye him not with fear but just normally. Jenny the teacher says, “They already have another world view. They know a lot of bad things about the world. They know about sexuality, abuse, and death. They come to their studies with a mountain of knowledge and prior learning. We just adjust this education to fit their surrounds.”

Homework done between sales. No time to lose.

“Because of work, many of them are not accustomed to dancing, to thinking, to choosing. We look at them as an achievement. Like when they dance or sing. Our first objective is to restore the magic of being able to dream. And then establishing a way they can achieve their dream,” says Lenina García.

Questioning Reality

According to the Survey of National Living Conditions (ENCOVI) and the International Labor Organization (ILO), in 2011 850,937 children were working in Guatemala. Child is defined as between the ages of seven and seventeen years old. Of those, 60 percent are under fourteen years old. It’s estimated that children produce twenty percent of Gross National Product (GNP).

Beside the notebook is today’s work.

“For the ILO, child work is an outdated practice that must be fully punished, equally dealt with everywhere. UNICEF’s focus, however, and even children’s protection organizations have turned that process on its head. They proceed from the view that to prevent or eradicate child labor the first step is to invest in education,” Garciá explains.

– What do you tell a child so that he or she can stop working?

– Our model focuses more on how boys and girls begin to question the reality that surrounds them. They begin to be agents of their reality and not its objects. If they work they have to know that this work is dignified and that they are not going to allow anybody to exploit their rights or abuse them. We try to plant this seed. This child is going to continue studying, continuing to educate themselves, and at some point the cycle will be broken, says García.

In DIGEEX, Estela Tavico, head of the Department of the Method (Modalidad) of Distance Education, emphasizes that in certifying a program like PENNAT, the Ministry is not supporting child labor. Not in its worst forms. “We acknowledge the value of work. We can’t deny that reality. We know that before these children have breakfast they have already sold fifty jocote, a box of gum, or made five corn tortillas. It’s work. Our task, however, is to provide education. We acknowledge the value of work. But our goal is to support an option among all these difficulties.”

By law MINEDUC cannot directly certify institutions like PENNAT. Its legal charter does not cover that type of education, with those sorts of characteristics. “As luck would have it, that’s where the DIGEEX – that’s where we come in. Since we are a subsystem of extra-scholarly education, we have other characteristics, other goals, other objectives, and a distinct nature. So, we can approach you and say, ‘Yes, it’s possible. We can and do support them.’ To support this population, the legal backing for that support occurs via a ministerial agreement,” explains Tavico.

The Ministry of Education (MINEDUC) does not think the results of success in these programs can be measured. Nor does it collect statistics on programs for adults and children over thirteen, those from the DIGEEX. Wendy Rodríguez, deputy director of educational projects puts it this way: “In the educational subsystems – in and outside school – there’s a unit that is specifically in charge of evaluation and research in education. It assesses math and language. Those are key indicators about how well things are turning out. However our programs – the ones that deal with overage children in accelerated primary and basic programs – are characteristically different: neither in terms of timetables nor calendars can they be seen as school-based. Since they work the whole year this difference has an implication for the statistics. There’s no beginning and no end. In 2013, participants numbered 72,098 people.”

That figure counts adults and children older than thirteen. The child workers of La Terminal were included.

They say at PENNAT that some of their graduated students “come back to teach.” Some have graduated as accountants, from high school, as teachers. García says that they are taught to be critical about the individual’s role in society, and sensitive to gender equality. “About a year ago on May Day (1 May) we celebrated with the working children. They came dressed as what they wanted to be later in life. There were teachers, secretaries, lawyers, and accountants. They want to pursue interesting professions. They don’t just want to be sellers.”

There’s no time for breaks. When school finishes, work begins.

– In terms of the decision to work, are there opportunities outside La Terminal market?

– You mean how to break the vicious cycle of child labor. It’s like giving them back a dream.

Education in the market means that La Terminal’s child workers don’t stay marginalized while they grow up.

Journalist Oswaldo J. Hernández reports for Plaza Publica. This article first appeared bearing the title, “Trabajar y estudiar en La Terminal para no quedar fuera del sistema,” and is available at: http://www.plazapublica.com.gt/content/nunca-creimos-que-crecer-nos-dejaria-fuera.

Translator Patrick Timmons is a human rights investigator and journalist. He edits the Mexican Journalism Translation Project (MxJTP), a quality selection of Spanish-language journalism about Latin America rendered into English. Follow him on Twitter @patricktimmons. The MxJTP has a FaceBook page: like it, here.