This article was first published on 9 January 2015. It has been translated without permission for the Mexican Journalism Translation Project.

The Abducted Journalist and the Mayor of Medellín, Veracruz

By Ignacio Carvajal (SinEmbargo)

(The first journalist abducted this year Moisés Sánchez of Veracruz, Mexico, was taken by armed men from his home in Medellín de Bravo on 2 January 2015. He has not yet been found. The Committee to Protect Journalists issued a press release summarizing the facts of Sánchez’s disappearance, demanding his return and the prosecution of his abductors. Veracruz is one of the most dangerous places in the Americas to practice journalism: CPJ reports that since 2011 three journalists have disappeared and the organization has documented the murders of nine other journalists.

Prior to Moisés Sanchez’s disappearance the mayor of Medellín had threatened the journalist. Days after Sánchez’s disappearance, the Associated Press reported that the entire municipal police force of Medellín de Bravo had been brought in for questioning by the Veracruz State Prosecutor with three of those officers detained.

Journalist Ignacio Carvajal reports from Veracruz on the story of the friendship and the fight between the journalist and the mayor of Medellín. – PT)

As a candidate he kissed children. He said hello to farmers and housewives. He walked the muddy streets of Medellín’s villages. He wore out his shoes and got thorns in his clothes in the rural areas. He promised that if he won he would jail his predecessors: Rubén Darío Lagunes and his putative political offspring Marcos Isleño Andrade, both of the Party of the Institutional Revolution (PRI). And he promised one more thing. Omar Cruz Reyes offered all the directorships and executive appointments to those born in the township: “Medellín for people from Medellín,” he used to say. But he did not fulfill that promise. Most of his cabinet was filled with people who lived in the Port of Veracruz and its bordering neighbor Boca del Río.

Omar Cruz is not a dyed-in-the wool PAN-ista. He became a candidate for the PAN thanks to efforts by his sister-in-law Hilda Nava Seseña and her uncle and aunt, Salustia Nava Seseña and Maurilio Fernández Ovando. The aunt is former president of the DIF [Mexico’s Children and Families Department] and the uncle is the former PANista Mayor of Medellín. Hilda was Maurilio Fernández’s personal assistant when he served as mayor.

At the same time, Omar Cruz Reyes created an organization bearing his initials (Organizando Contigo el Rumbo – literally translated as Organizing the Future With You) to work with the residents of the new subdivisions, like Arboleda San Ramón Puente Moreno and Casa Blanca. Both places bring together thousands of voters, mostly from Veracruz and Boca del Río).

Before the 2010 local elections, and to keep himself on the lips of voters, Cruz began a media campaign demonstrating against mayors Marco Isleño Andrade (2010 – 2013) and Rubén Darío Lagunes (2007 – 2010); primary school students made fun of Lagunes at school events because he dallied when he gave speeches.

There were at least three protests where Omar Cruz attacked Marcos Isleño Andrade for absent public works, missing support and neglect by the municipality. Invariably the journalist Moisés Sánchez attended these protests. He saw Omar Cruz – when he entered politics he was just 27 – as without bad political habits, without “a tail to be tugged”, well spoken, educated, from the working middle class and a rousing speaker against Marcos Isleño and in favor of citizens. The men clicked. And Moisés Sánchez began following him through the streets and writing stories about his promises and his projects. At last a young person from El Tejar – Medellín’s most important area – was willing to fight back against the corrupt politicians.

In the spirit of “Medellín for people from Medellín,” Omar Cruz offered Moisés Sánchez the position of press officer if he made it into the mayor’s office. That’s what Sanchez’s colleagues said; it was his big dream back in those days: to be his town’s press officer at city hall.

CRUZ TURNED HIS BACK ON THE PAN

He had just won office as mayor when Omar Cruz turned his back on the PAN and his campaign promises, remembers a city employee who preferred to remain anonymous. Photo: Special

He’d barely won but he started reneging on his promises. He gave the post promised to the journalist to a person from the port of Veracruz. The salaries weren’t what he had promised. Neither were the responsibilities, nor the secretaries and support staff. The important posts stayed in the hands of citizens from the conurbation of Veracruz-Boca del Río and did not go to the professional activists in Medellín’s Partido de Acción Nacional (National Action Party, or, PAN). This young businessman’s promises were soon spent and many sunk. “Many people support him but it’s out of necessity, because their salaries aren’t enough,” said one city employee who commented on condition of anonymity.

On the campaign trail Omar Cruz was a different person from the one he became when mayor elect. He stood on the same platform as Julen Rementería and Oscar Lara, respectively the former mayor of Veracruz and a former PAN-ista legislator. This couple are credited with bringing Omar Cruz over to Governor Javier Duarte, to the PRI and to “red PANism” – the term, panismo rojo is a colloquial expression for a bloc of PAN-istas who fight the government of Veracruz with one hand but with the other support every move by Javier Duarte as governor. (Translator’s note: the PAN’s color is blue.)

The gap between Omar and the PAN-istas in Veracruz’s state capital, Xalapa, and with the Yunes [a political family in Veracruz with links to both the PAN and the PRI] soon widened. On one day he was seen close to Raúl Zarrabal, PRI legislator for Boca del Río on Wednesday when visiting his constituents, the next day he was with the PRI-ista side of the Yunes and the following day he was with a representative of the government of Veracruz.

Omar Cruz’s ties to Governor Duarte grew stronger because of the issues surrounding the Metropolitan Water and Sanitation System (SAS), a para-municipal organization that regulates and administers sanitation and water supply in the Veracruz-Boca del Río-Medellín conurbation. Its management of millions of pesos of resources has always been opaque.

In the middle of 2014, the mayor of Boca del Río, Miguel Ángel Yunes Márquez threatened breaking away from the SAS so that his city could administer its own municipal infrastructure. Independently of this threat, Yunes Márquez had provided evidence of the overwhelming corruption in the SAS since Yolanda Carlín’s time as its director. There were dozens of Carlín-friendly journalists on her payroll, leaders of PRI neighborhoods, among others. But the real debacle began when José Ruiz Carmona arrived on the scene. Carmona was a PRI-ista who had held many public posts and had concluded an undergraduate degree in record time. Governor Javier Duarte modified the law so that Ruiz Carmona could manage the SAS.

Ruiz Carmona ended his time at the top of the organization with blackouts for failure to pay bills, protests over uniforms for workers and complaints made to its union by pilots, lovers, wives and family members belonging to both the PRI and the PAN, all of whom were on the payroll or well-connected. Javier Duarte ignored the financial shambles left by Ruiz Carmona and brought him into his cabinet, naming him undersecretary for Human Development in the Ministry of Social Development (SEDESOL).

In this context and so as to establish order in the SAS, Yunez Márquez was waiting for support from Omar Cruz against the only PRI-ista on the organization’s board, Ramón Poo, the mayor of the Port of Veracruz. Instead, he deserted Yunes Márquez to support the SAS plan to create another organization, passing over Ruiz Carmona and other former directors.

Omar Cruz attended every event in the Port of Veracruz and Boca del Río at which Duarte appeared, looking for a moment, even if just a hello, with the governor.

Around Medellín, Omar Cruz assumed a friendship with Javier Duarte. “We understand society’s problems because we are both young,” he was heard to say. Now the governor won’t even answer his phone calls.

Back in 1812, in this municipality, army officer and ex-President Nicolás Bravo spared the lives of 300 Spanish combatants who had fallen prisoner in the Wars for Independence. That’s why Medellín is called Medellín de Bravo. It doesn’t look like Omar Cruz is going to have luck similar to that of the Spanish.

In Veracruz the worst state to practice journalism in the Americas, a place toxic for reporters, Moisés Sanchez’s abduction is the first time a high profile culprit has been accused of a crime against freedom of expression. The PRI-ista state government of Veracruz sees an opportunity to strike a blow against the PAN in the conurbation of Veracruz-Boca del Río-Medellín as it prepares for the 2015 federal elections.

Today, up to press deadline, not one PAN-ista heavyweight has spoken out in support of Omar Cruz. Not at the state level and there’s not a peep from Julen Rementería or Oscar Lara. Medellín’s PAN-istas have withdrawn into themselves, mute, watching everything and letting the guillotine fall into the hands of the prosecutor, Luis Ángel Bravo, who is aiming for Omar Cruz’s neck.

THE ABARCA OF MEDELLÍN’S MANGO ORCHARDS

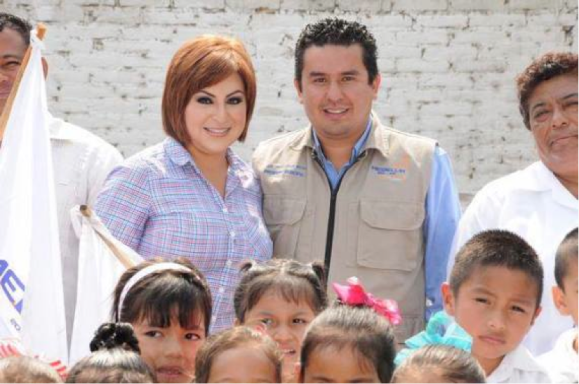

Since the disappearance of Moisés Sáncez, people in Veracruz have compared Mayor Omar Cruz and his wife, Maricela Nava to the Mayor of Iguala, Guerrero and his wife. Photo: Twitter @HaytodeMedellin

Since the disappearance of Moisés Sáncez, people in Veracruz have compared Mayor Omar Cruz and his wife, Maricela Nava to the Mayor of Iguala, Guerrero and his wife. Photo: Twitter @HaytodeMedellin

Another person passed over by Omar Cruz says, “The best jobs and salaries went to his friends. He sidelined the current PAN-istas and he gave them lesser jobs with low salaries. That was the constant complaint. In my case I left because of the pay. He promised me 12,000 pesos a month as a director (US$820) but I got half that. When I complained about the shortfall to Omar Cruz he wouldn’t talk to me. He sent me to his wife, Maricela Nava Seseña, the DIF president.”

Since what happened to Moisés Sánchez, both Maricela Nava and Omar Cruz have been compared to the Abarca, the mayor and his wife from the state of Guerrero [alleged to have masterminded the disappearances of the 43 student teachers of Ayotzinapa]. In this Veracruz municipality of major mango cultivation, Cruz and Nava ruled during the day and night, and people from the state have labeled them “the Abarca of the Mango Orchards.”

Inside the municipal building, in fact, they say that Omar Cruz does not decide anything without first going through Maricela Nava and her sister, Hilda Nava Seseña. Omar Cruz made his sister in law the municipal secretary.

The three live under the same roof in the Residencial Marino in Boca del Río where the cheapest houses sell for 1.5 million pesos (US$100,000) — and that’s the price of some of the more austere properties. The upscale residential neighborhood is five minutes from Plaza El Dorado, currently one of Veracruz’s most exclusive malls, frequented by those Veracruz magnates who arrive in their yachts – it has a marina – to buy cinema tickets for a matinée or to lunch in one of its restaurants.

The neighborhood is lined with beautiful trees. It is connected to the highway with panoramic views of the beaches in Vacas-Boca del Río. There are mansions, large salons for special events, estates with country houses and staff on hand for a relaxing weekend, all lining the backwater of the River Jamapa.

Omar, Maricela and Hilda ride around in this year’s trucks. The three use bodyguards and together they attend sessions with spiritualists.

“In the first few days after taking office, several spiritualist consultants – witches – arrived to cleanse the place,” the source says.

They focused their efforts on expelling the bad vibes from the mayor’s office, occupied for six years by PRI-istas. They placed quartz, burned incense, copal and every sort of mélange making it smell like a market.

Once the bad spirits had left, the mayor ordered a giant portrait hanged: underneath the image in large letters appears the name, “Javier Duarte de Ochoa, constitutional governor of Veracruz.”

In that office, on another wall, another black and white image bearing large letters: OMAR CRUZ, PRESIDENTE MUNICIPAL.

And decorating the surrounds in his office are numerous photos of Cruz along with his wife and sister in law.

In the mayor’s office, they say, Maricela Nava Seseña – known as the Queen of Medellín – became accustomed to issuing instructions and telling off campaign workers.

“Why are you asking for so much money from my husband? Are you really so great or are you his lover?” That’s what the first lady of Medellín said to staffers who complained about the low level of their salaries to Omar Cruz.

When dealing with labor issues, the mayor did not personally deal with them. He hung up the phone, referring them to his wife or his sister-in-law.

That’s what the former DIF director, Paula Aguilar Tlaseca experienced. She was one of the first to jump ship because of the poor treatment, low salary and little professional recognition from the Abarca of Medellín de Bravo.

When dealing with complaints in citizen-related issues, the protests did not mean much to them. “Protest all you like. I am the mayor,” Cruz replied when his staff advised him that social problems such as the new annual charge for public cleaning were turning into flash points of unrest.

Omar Cruz offered Moisés Sánchez the position of press officer if he won election as mayor. However, a little after the election the conflicts between the men began until, according to one witness, the mayor threatened the journalist. Photo: Special.

In Moisés’ last protest outside the Medellín municipal building in the middle of last December he complained about this new municipal tax and the increase in common crime. It was a bitter encounter with Omar Cruz. A strange thing, too, since the mayor never confronted his critics.

“Why are you protecting criminals?” Moisés dared to ask Omar. It has been forty-eight hours since the owner of a convenience store had been murdered, his truck taken.

“I am not protecting them. I am fighting them. I asked for help from the Mando Único [the unified state command of public safety agencies] and the Marines,” Omar Cruz replied. But Moisés was not satisfied and continued in a loud voice with his criticism until one of Cruz’s staff, Juanita León slapped Moisés Sanchez several times on the cheeks.

Omar Cruz did not do anything else. But he left without offering Moisés an apology and failing to scold his employee who had hit him. Instead, a friend of Moisés told his family that the mayor threatened the journalist…

“Take care. Omar says that he wants to frighten you.”

Ignacio Carvajal is a prize-winning journalist working in Veracruz. Follow him @nachopallaypaca on Twitter. In Latin America Carvajal is recognized as a skilled practitioner of the crónica, a form of reporting news by telling a story. Check out his “Ranch of Horror” in translation for the Mexican Journalism Translation Project. This article was first published under the title, “Aliado de Duarte, cliente de “brujos”, el Alcalde del PAN puso la mira en periodista,” available at: http://www.sinembargo.mx/09-01-2015/1212468.

Translator Patrick Timmons is a human rights investigator and journalist. He edits the Mexican Journalism Translation Project (MxJTP), a quality selection of Spanish-language journalism about Latin America rendered into English. Follow him on Twitter @patricktimmons. The MxJTP has a Facebook page: like it, here.